STIGMA: “A MARK OF DISGRACE OR INFAMY”

The impact of stigmatization in preventing the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Sub-Saharan Africa

By Michelle Tsui

Permissions granted from Youth Challenge Institute www.yci.org

HIV began its well-recorded spread through Sub-Saharan Africa in 1959 when the earliest known HIV infection was found in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Fifty years later, HIV has grown into a global epidemic infecting more than 33.3 million individuals worldwide according to the World Health Organization, 22.4 million of whom call Sub-Saharan Africa their home.

The HIV/AIDS epidemic began in Sub-Saharan Africa in the late 1970s, soon after the African independence movements brought displaced refugees, civil wars and poverty. This created an ideal setting for the sexually transmitted disease to spread. Since then, Sub-Saharan Africa has remained at the top of the charts in terms of the HIV infected population for reasons including forced prostitution for income, transmission of HIV from mother to child, the concept of concurrency, and most importantly, the social stigma against HIV that effectively counters the attempts of prevention and treatment.

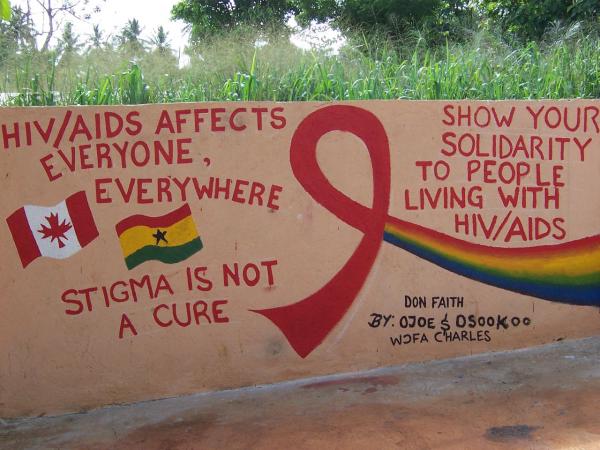

In almost any nation around the world, the HIV/AIDS infection is associated with some level of stigma, or “mark of disgrace or infamy”. United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon states, “Stigma remains the single most important barrier to public action. It is a main reason why too many people are afraid to see a doctor to determine whether they have the disease, or to seek treatment if so. It helps make AIDS the silent killer, because people fear the social disgrace of speaking about it, or taking easily available precautions.”

Especially in certain parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, HIV/AIDS is taboo due to its association with physically promiscuous activities, and stigmatization toward infected individuals has become normalized and infused in those communities. As a result, individuals that are known to be living with the HIV/AIDS infection face prejudice, maltreatment, abuse, and discrimination even from their friends and family. Two specific cases of stigmatization were reported in the International Quarterly of Community Health Education (2009) when a boy named Nkosi Johnson was refused entrance to school and when a woman named Gugu Dlamini was murdered in South Africa by a mob that found out she was HIV positive.

HIV/AIDS-related social stigma, often cause individuals often shy away from treatment, medication, and care, even if such things may well increase their life expectancy. The overpowering fear of discrimination and condemnation from loved ones makes it difficult for people to come to terms with and manage the disease personally. However, this personal attitude becomes a problem for the entire nation when people refuse to get tested or disclose their infected condition to their romantic partners, causing the epidemic’s continuation.

In a recent study performed by the Africa-UCSF HIV/AIDS Stigma Project (2009), stigma was quantitatively measured in five different African countries using a series of surveys completed by people living with HIV and nurses treating HIV patients. The survey asked questions such as “In the past three months, how often did the following event happen because of your HIV status?” and determined the frequency of stigma-related occurrences. The results showed that 64.2% of all HIV infected individuals and 83.7% of nurses reported experiencing one or more HIV stigma events in a period of 3 months in all five African countries. Fortunately, the study also showed that in all five countries, stigma incidents decreased in the HIV infected over the time of the study; however, further study is needed to determine exactly why this is the case.

The most obvious solution for stopping stigma’s affects on the epidemic would be to break the myths and educate the community about disease prevention and availability of treatment. The World Health Organization states, “As HIV/AIDS becomes a disease that can be both prevented and treated, attitudes will change, and denial, stigma and discrimination will rapidly be reduced.” According to a related study conducted in Botswana, “stigmatizing attitudes had lessened three years after the national program providing universal access to treatment was introduced.” However, increased access to treatment will not by any means eliminate the social stigma the HIV infection brings.

To address the social stigma, countries are creatively promoting awareness of the ability to live a normal life even with HIV/AIDS. The documentary Miss HIV depicts the true stories of everyday citizens in Sub-Saharan Africa who are battling stigma in unique ways. In Botswana, the Miss HIV Stigma-Free beauty pageant strives to show the community that women with HIV are still human beings and should be treated with respect. In Uganda, college students rally together in order to break the stigma surrounding sexual abstinence, as well as to collect interviews from people that that have chosen to publicly admit their HIV positive status and encourage those infected to get medicine as soon as possible. The winner of the Miss HIV Stigma-Free beauty pageant, Ms. Ntsepe proclaims, “I’m going around the country to talk to people to say that (being) an HIV positive person does not mean you have done something wrong. You are still who you are.”

Getting rid of social stigma in Sub-Saharan Africa may seem like impossibility, but it can be done. Ban Ki Moon believes, “We can fight stigma. Enlightened laws and policies are key. But it begins with openness, the courage to speak out.” HIV education and awareness needs promotion so that people will seek treatment, get tested, and take measures toward HIV prevention. Once myths are destroyed, fear is eliminated, and the “mark of disgrace or infamy” erased, the HIV epidemic will be one giant step closer to elimination.

**********

Author Bio:

Michelle Tsui is a first year intended public health major planning to pursue the fields of epidemiology and infectious disease. In her free time she loves reading, outdoor activities, and playing board games with friends.