This article was originally published in our Fall 2018 print issue.

“If citizens don’t demand evidence-based decisions from their political leaders,” says Dr. Charlotte Smith from UC Berkeley’s School of Public Health, “those leaders have no incentive to create policy based on facts.”

By the very nature of their scope, public health initiatives involve large-scale decision-making. Policymakers are often forced to make determinations not on individual anecdotes and circumstances, but on general population trends.

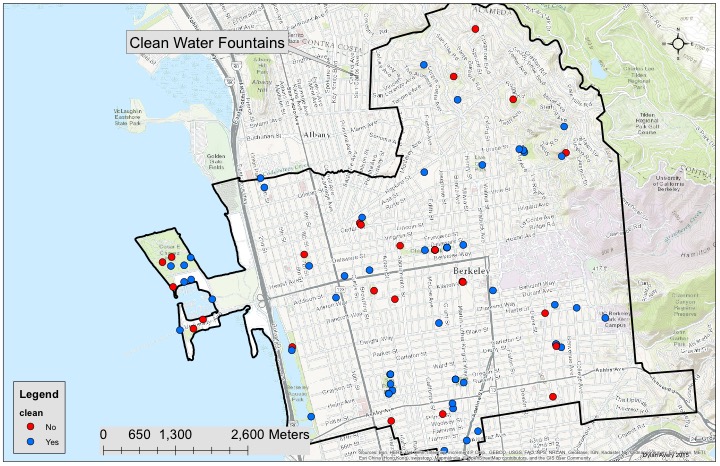

However, legislation aiming to improve society doesn’t always mean that individual citizens have equal access to these benefits. Access to safe, clean, and public drinking water across Berkeley is one such example. Partnering with former City Councilmember Laurie Capitelli, Smith is setting out to assess the availability of public water fountains throughout the City.

Berkeley’s soda tax levies an additional charge on sweetened beverages, from Coca-Cola products to sugary energy drinks such as Gatorade. The idea behind the extra charge on these beverages is that it would incentivize consumers to drink water rather than a sugar-filled drink.

While this seems ideal in theory, such regressive taxes disproportionately affect people who don’t have access to an alternative choice — in this case, clean water. Even after the tax was implemented, Capitelli found that people were still purchasing unhealthy drinks instead of using water fountains. While discussing the problem with Smith, Capitelli mentioned that there was no existing map of water fountains in the area. This led Smith to suggest that her class create a database cataloging the location and condition of public water fountains in Berkeley using GIS, or geographic information systems.

Water fountain cleanliness, as well as 10 other variables like functionality and accessibility, was mapped using GIS. Students in Smith’s class collected data from 23 inventory zones inside Berkeley city limits.

IMAGE COURTESY OF CHARLOTTE SMITH

The outcome of this project is detailed in a research paper published by Smith and co-author Dylan Avery in BMC Public Health this past year. While a lot can be learned from the initiative itself, there are some underlying lessons in the approach used by Smith and her class that citizens, not just students, can use to build an advocacy platform to make changes within community health.

Our communities deserve an administration that studies the facts of environmental health and understands how government policies can directly affect real people, not just abstract constituents. Although this seems like a daunting task for any individual, using a method like GIS, which can help us identify broad trends, is a great way to start identifying community-wide patterns.

As with any tool, GIS can be used positively or negatively. While crowd-sourcing data from the community seems like a great way to elicit active participation from citizens, we have to be careful that nobody, intentionally or accidentally, misrepresents the data. In addition to public health professionals who can use GIS to aid community groups, there are free online tutorials available on platforms such as Esri. Smith maintains that increasing numbers of elementary through high school students across the country are learning GIS in the classroom, indicating that it could soon be as prevalent an educational tool as Microsoft Word or Excel.

“Everything happens somewhere,” reminds Smith. We miss a large piece of the puzzle if we exclude location from our calculations. Location simultaneously enables and restricts us: Even in the 21st century, we are limited by where we live, as it determines what we have access to.

Most public health problems revolve around access, so combining this knowledge with an analysis of patterns and trends is a good place to identify problems in the community. As Berkeley students, we have amazing tools at our disposal, from state-of-the-art software down to the smartphones in our pockets, which is how Smith’s students collected their data. It is necessary to know how to use these tools, but it is more important that we know why.

Understanding how we fit into the larger community enables us to understand the relationships between broad trends and individual people. And that is what public health is all about.